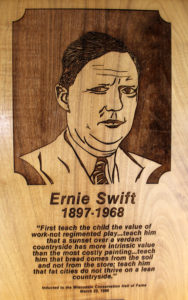

1897 – 1968

Inducted 1986

“First teach the child the value of work, not regimented play…teach him that a sunset over a verdant countryside has more intrinsic value than the most costly painting…teach him that bread comes from the soil and not from the store.” — Ernest Swift

“First teach the child the value of work, not regimented play…teach him that a sunset over a verdant countryside has more intrinsic value than the most costly painting…teach him that bread comes from the soil and not from the store.” — Ernest Swift

“A successful game warden was by nature an individualist, a man not afraid to walk alone through cold, dark woods, fields and marshes to uphold the law.” So wrote Ernie Swift, and he surely knew of what he wrote. Swift developed a reputation as a fearless game warden in Wisconsin’s northwoods during the 1920s and 1930s.

Not surprisingly, Swift was also unafraid to walk ahead of the crowd as his career in conservation evolved. In the 1930s, he forged a lasting professional and personal relationship with Aldo Leopold (WCHF Inductee). Swift was then deputy director of the Wisconsin Conservation Department. He and Leopold fought the deer management battles of the early 1940s, arguing that scientific research should guide management to the herd and the ecosystem. This put Swift at odds with old colleagues, but he forged ahead. His work on management of the deer herd is credited with helping set the state for further wildlife management refinements.

Swift was appointed director of the Conservation Department, the forerunner of today’s Department of Natural Resources, in 1947. He was uncompromising in his efforts to preserve the state’s natural resources, no easy task in the days before there was strong public support for protecting resources.

Swift was appointed director of the Conservation Department, the forerunner of today’s Department of Natural Resources, in 1947. He was uncompromising in his efforts to preserve the state’s natural resources, no easy task in the days before there was strong public support for protecting resources.

His career went to the national level in 1954 when he was appointed assistant director of the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, DC. A year later, he accepted the appointment as director of the National Wildlife Federation.

Swift was raised on the windswept prairies of southwestern Minnesota. His years on the family farm honed a vivid imagination, and he credited those years with helping him to develop a deep understanding of the importance of conservation.

Because Swift was well able to communicate what he knew he was an excellent speaker and writer. His autobiography A Conservation Saga was published in 1967, a year before he died. It can still be found in stacks of libraries across the state.

Nature was Ernie Swift’s teacher — he never received a forma college education, yet he rose to positions of state and national importance in the conservation movement. “People become conservationists in relation to their ability to become philosophers,” Swift wrote. Tough, self-taught and dedicated, Swift has left his own special conservation legacy in a state with a rich conservation history.

Resources

Ernest Swift Biography by Angela Cannon

Ernie Swift, article in Wisconsin Natural Resources, 1979

Ernest Swift, National Wildlife Federation Conservation Hall of Fame, 1979

State of Wisconsin Natural Resources Board Memorial Resolution – Ernest F. Swift, Conservation Bulletin, 1968

Ernest Swift Named as Fish and Wildlife Service Assistant Director, Fish and Wildlife Service Press Release, 1954

Wisconsin’s Forests, booklet with letter from Ernest F. Swift, Wisconsin Conservation Department Director. Resource donated by Ernest J. Bauer who served on the Conservation Congress for many years

Ernest Fremont Swift 1897-1968, biography

Ernie Swift, article

Deer: Conservation’s Longtime ‘Problem Child’ for Wisconsin, article by Patrick Durkin, 2020

Ernie Swift – History of Swift Nature Camp

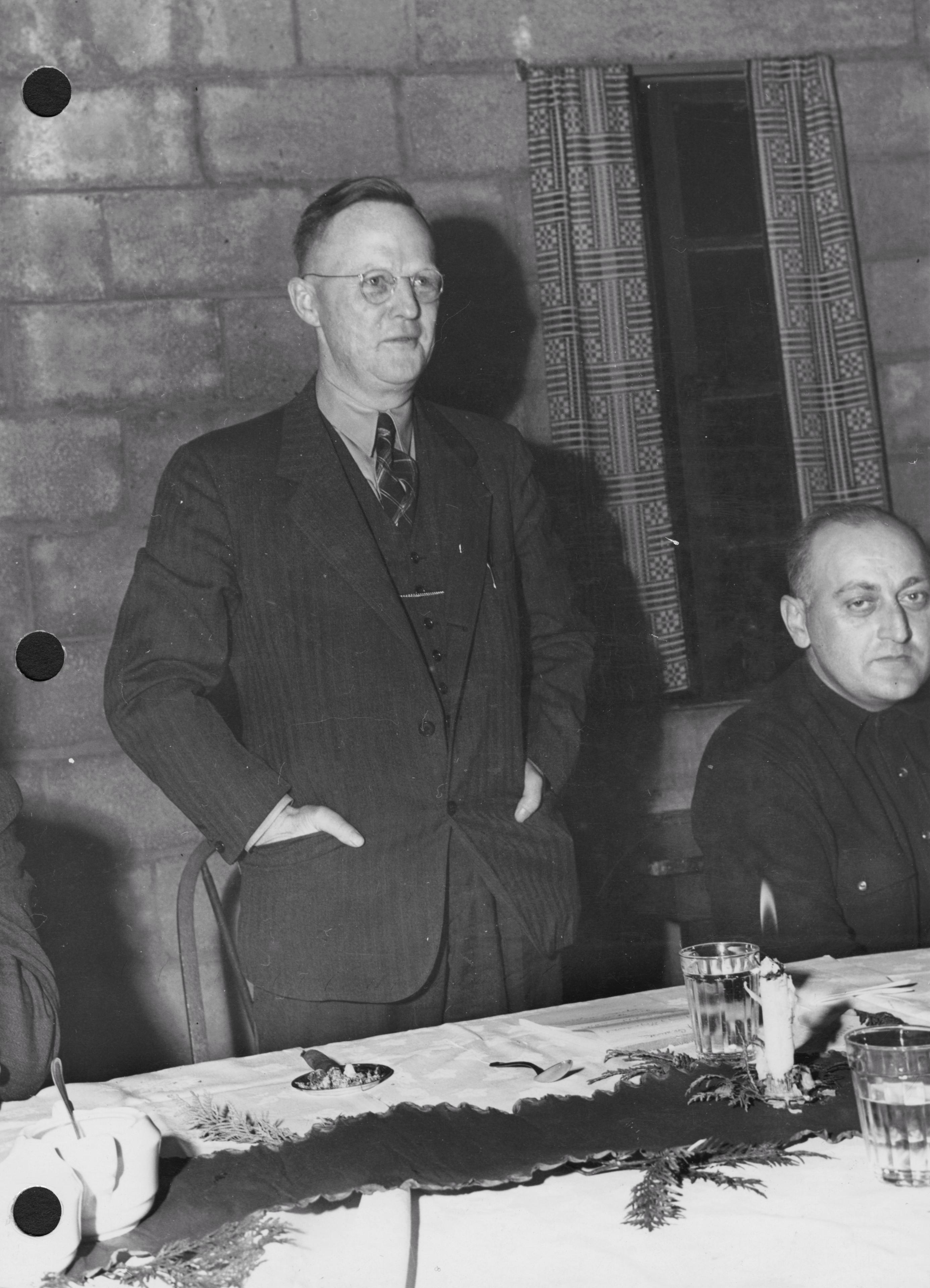

Photos

These images may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.